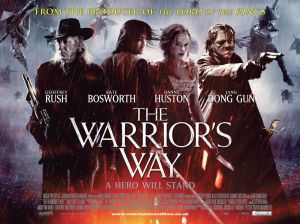

Image Credit: http://crankleft.com/files/the-warriors-way-1.jpg

This Monday Tuesday Mini March Past is solely to express my love for the film The Warrior’s Way, so there won’t be any ties to theory I’ve covered on the blog (I do discuss some other theory, so don’t despair). At this point, you should know how these posts work: brief synopsis followed by stuff that I like in the film.

*Spoilers for The Warrior’s Way follow below the trailer!*

Synopsis

This film tells the story of a ninja assassin named Yang (Jang Dong-Gun), in the 19th century, who becomes “the greatest warrior in the history of world ever” (the film’s phrasing). He is a member of a clan called The Sad Flutes (the sound the victim makes after the throat has been cut) and he is at war with a rival clan. He kills every member of the rival clan except for an infant girl, whom he can’t bring himself to murder. Instead, he runs away with her, which brings the fury of his own clan down upon him. He heads to the American West to meet up with an old ninja outlaw buddy. When he arrives in Lode, the Paris of the West, he finds the town is largely falling apart and his friend has since passed away. He meets a bevy of interesting carnival folk, including a knife thrower named Lynne (Kate Bosworth), a ring leader dwarf named 8-ball (Tony Cox), and Ron (Geoffrey Rush), the town drunk. As you might guess, Yang makes a new life in Lode with his new friends. As he gets to know his new companions, though, he finds that tragedy lies in their pasts as well. Lynne’s entire family was killed by a madman called The Colonel (Danny Huston, of course!) and Ron lost the love of his life long ago because of his gun-totin ways. The end of the film sees the town and their new ninja friend band together to take on The Colonel’s outlaws as well as Yang’s former master and an army of ninjas. Swordplay, gunfights, and bloodshed take center stage in the final moments of a surprisingly fun film.

Image Credit: http://www.filmofilia.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/warriors_way_01.jpg

Image Credit: http://www.aceshowbiz.com/images/still/the_warrior_s_way17.jpg

Warriors in the Gutters: A Story of Many Visuals and Few Words

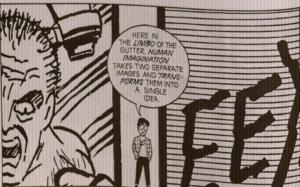

Yang, unsurprisingly, is a man of few words. I say unsurprisingly for a number of reasons ranging from the character trope (the stoic warrior) to simple language barrier. Beyond him, though, most characters are people of few words (Geoffrey Rush’s character being an exception). The film is told through visual sequences. Thinking on it now, it is quite similar to a comic book, and I mean that in a good way. Comics use panes filled with visuals to tell their stories with text bubbles used sparingly. According to Scott McCloud, comics use the concept of gutters (the space between panes) to help tell their stories. Naturally, comics can’t draw every single movement, so they rely on reader imagination to fill in scenes, granting the reader a level of active agency in the story. In these gutter spaces between panes, readers mentally complete the actions begun in the previous panel. McCloud uses gutters to argue that people think in terms of stories or narratives.

Image Credit: Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, by Scott McCloud

Other theorists make this same argument; take a look at Joseph Campbell’s work sometime, or, better yet, check out my buddy jeezuswords’ post about Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces for excellent summary and commentary on the work. Obviously, a film doesn’t use gutters in the same way that comics do, but The Warrior’s Way does reach a semblance of gutters in some scenes. For example, early in the film, Yang confronts a line of ninjas. The scene shows him take a step forward and speeds up. He blurs through the line and slows down when he reaches the end. Everything remains as it was the moment before until red clouds spurt out from the necks of the ninjas he just fastforwarded through. In this case, the scene is too fast to allow the viewer to actually see the actions Yang performs. Instead, we get the before and after scene, and through those visuals, our minds fill in the gaps.

The visuals also tell the tragedies of our main characters, Yang and Lynne. Both are told in vivid colors—Yang’s with blues and blacks, and Lynne’s with browns and reds. Yang’s past is fast paced and filled with action while Lynne’s, at the critical moment, when she is shot in the back by The Colonel, is slowed down. Both past stories emphasize the faces of these characters. Yang’s often wrought in torturous pain from his training. The final image we have of Lynne’s past is her lying on the ground after being shot and watching her family murdered. A blood-filled tear streams down the side of her face, its red color standing out against her pale skin and multi-colored eyes. The contrasting visuals of these pasts are brought together in the film’s present, most notably in the “dance scene.” In this scene, we see the brilliant tapestry of the blue-black night sky against the dark desert with Yang and Lynne “dancing.” It’s a visually impressive scene. Check it out below:

It actually reminds me of the scenes I describe in my first Monday Mini March Past about the Wii game The Last Story. Anyway, as you can see from the clip, the visuals play a role here to evoke mood and advance the story of these two scarred characters. Tragedies fill their pasts and seemingly culminate with each finding a form of catharsis with the other in this scene.

Like Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters, I love this film. Most people applaud its blending of genres—martial arts/ninjas/samurai with westerns (both American and spaghetti). I confess to knowing too little about either genre to make an intelligent comment on that particular element. Instead, I love this film for the evocative visuals, the cinematography, etc. The visuals do much to enhance and even tell the story. It’s worth seeing for the visuals alone. I recommend it!

Work Cited:

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins, 1993. Print.